|

Welcome! Click on me and I will take you to one of the Life Guides. May they be greatly beneficial for you. |

|

Contents |

Preface 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40: 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 |

Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramhansa Yogananda

Chapter 44: With Mahatma Gandhi at Wardha"Welcome to Wardha!" Mahadev Desai, secretary to Mahatma Gandhi, greeted Miss Bletch, Mr. Wright, and myself with these cordial words and the gift of wreaths of khaddar (homespun cotton). Our little group had just dismounted at the Wardha station on an early morning in August, glad to leave the dust and heat of the train. Consigning our luggage to a bullock cart, we entered an open motor car with Mr. Desai and his companions, Babasaheb Deshmukh and Dr. Pingale. A short drive over the muddy country roads brought us to Maganvadi, the ashram of India's political saint.

Mr. Desai led us at once to the writing room where, cross-legged, sat Mahatma Gandhi. Pen in one hand and a scrap of paper in the other, on his face a vast, winning, warm-hearted smile!

"Welcome!" he scribbled in Hindi; it was a Monday, his weekly day of silence.

Though this was our first meeting, we beamed on each other affectionately. In 1925 Mahatma Gandhi had honored the Ranchi school by a visit, and had inscribed in its guest-book a gracious tribute.

The

tiny 100-pound saint radiated physical, mental, and spiritual health.

His soft brown eyes shone with intelligence, sincerity, and discrimination;

this statesman has matched wits and emerged the victor in a thousand

legal, social, and political battles. No other leader in the world

has attained the secure niche in the hearts of his people that Gandhi

occupies for India's unlettered millions. Their spontaneous tribute

is his famous titleMahatma, "great soul."1

For them alone Gandhi confines his attire to the widely-cartooned

loincloth, symbol of his oneness with the downtrodden masses who

can afford no more.

"The ashram

residents are wholly at your disposal; please call on them for any

service." With characteristic courtesy, the Mahatma handed

me this hastily-written note as Mr. Desai led our party from the

writing room toward the guest house.

Our guide led

us through orchards and flowering fields to a tile-roofed building

with latticed windows. A front-yard well, twenty-five feet across,

was used, Mr. Desai said, for watering stock; near-by stood a revolving

cement wheel for threshing rice. Each of our small bedrooms proved

to contain only the irreducible minimuma bed, handmade

of rope. The whitewashed kitchen boasted a faucet in one corner

and a fire pit for cooking in another. Simple Arcadian sounds reached

our earsthe cries of crows and sparrows, the lowing of cattle,

and the rap of chisels being used to chip stones.

Observing

Mr. Wright's travel diary, Mr. Desai opened a page and wrote on

it a list of Satyagraha2

vows

taken by all the Mahatma's strict followers (satyagrahis): "Nonviolence;

Truth; Non-Stealing; Celibacy; Non-Possession; Body-Labor; Control

of the Palate; Fearlessness; Equal Respect for all Religions;

Swadeshi (use of home manufactures); Freedom from Untouchability.

These eleven should be observed as vows in a spirit of humility."

Two

hours after our arrival my companions and I were summoned to lunch.

The Mahatma was already seated under the arcade of the ashram porch,

across the courtyard from his study. About twenty-five barefooted

satyagrahis were squatting before brass cups and plates. A community

chorus of prayer; then a meal served from large brass pots containing

chapatis (whole-wheat unleavened bread) sprinkled with ghee;

talsari (boiled and diced vegetables), and a lemon jam.

The

Mahatma ate chapatis, boiled beets, some raw vegetables,

and oranges. On the side of his plate was a large lump of very bitter

neem leaves, a notable blood cleanser. With his spoon he

separated a portion and placed it on my dish. I bolted it down with

water, remembering childhood days when Mother had forced me to swallow

the disagreeable dose. Gandhi, however, bit by bit was eating the

neem paste with as much relish as if it had been a delicious

sweetmeat.

The afternoon brought an opportunity for a chat with Gandhi's noted

disciple, daughter of an English admiral, Miss Madeleine Slade,

now called Mirabai.3

Her strong,

calm face lit with enthusiasm as she told me, in flawless Hindi,

of her daily activities.

We

discussed America for awhile. "I am always pleased and amazed,"

she said, "to see the deep interest in spiritual subjects exhibited

by the many Americans who visit India."4

Mirabai's

hands were soon busy at the charka (spinning wheel), omnipresent

in all the ashram rooms and, indeed, due to the Mahatma, omnipresent

throughout rural India.

Our

trio enjoyed a six o'clock supper as guests of Babasaheb Deshmukh.

The 7:00 P.M. prayer hour found us back at the Maganvadi

ashram, climbing to the roof where thirty satyagrahis were

grouped in a semicircle around Gandhi. He was squatting on a straw

mat, an ancient pocket watch propped up before him. The fading sun

cast a last gleam over the palms and banyans; the hum of night and

the crickets had started. The atmosphere was serenity itself; I

was enraptured.

A

solemn chant led by Mr. Desai, with responses from the group; then

a Gita reading. The Mahatma motioned to me to give the concluding

prayer. Such divine unison of thought and aspiration! A memory forever:

the Wardha roof top meditation under the early stars.

I agreed wholeheartedly.5

The Mahatma

questioned me about America and Europe; we discussed India and world

conditions.

"The

Wardha mosquitoes don't know a thing about ahimsa,6

Swamiji!" he said, laughing.

The

following morning our little group breakfasted early on a tasty

wheat porridge with molasses and milk. At ten-thirty we were called

to the ashram porch for lunch with Gandhi and the satyagrahis.

Today the menu included brown rice, a new selection of vegetables,

and cardamom seeds.

Three

daily rituals are enjoined on the orthodox Hindu. One is Bhuta

Yajna, an offering of food to the animal kingdom. This ceremony

symbolizes man's realization of his obligations to less evolved

forms of creation, instinctively tied to bodily identifications

which also corrode human life, but lacking in that quality of liberating

reason which is peculiar to humanity. Bhuta Yajna thus reinforces

man's readiness to succor the weak, as he in turn is comforted by

countless solicitudes of higher unseen beings. Man is also under

bond for rejuvenating gifts of nature, prodigal in earth, sea, and

sky. The evolutionary barrier of incommunicability among nature,

animals, man, and astral angels is thus overcome by offices of silent

love.

The

other two daily yajnas are Pitri and Nri. Pitri

Yajna is an offering of oblations to ancestors, as a symbol

of man's acknowledgment of his debt to the past, essence of whose

wisdom illumines humanity today. Nri Yajna is an offering

of food to strangers or the poor, symbol of the present responsibilities

of man, his duties to contemporaries.

In

the early afternoon I fulfilled a neighborly Nri Yajna by

a visit to Gandhi's ashram for little girls. Mr. Wright accompanied

me on the ten-minute drive. Tiny young flowerlike faces atop the

long-stemmed colorful saris! At the end of a brief talk in

Hindi7

which I was giving outdoors, the skies unloosed a sudden downpour.

Laughing, Mr. Wright and I climbed aboard the car and sped back

to Maganvadi amidst sheets of driving silver. Such tropical

intensity and splash!

The

Mahatma's remarkable wife, Kasturabai, did not object when he failed

to set aside any part of his wealth for the use of herself and their

children. Married in early youth, Gandhi and his wife took the vow

of celibacy after the birth of several sons.8

A tranquil heroine in the intense drama that has been their life

together, Kasturabai has followed her husband to prison, shared

his three-week fasts, and fully borne her share of his endless responsibilities.

She has paid Gandhi the following tribute: I

thank you for having had the privilege of being your lifelong companion

and helpmate. I thank you for the most perfect marriage in the world,

based on brahmacharya (self-control) and not on sex. I thank

you for having considered me your equal in your life work for India.

I thank you for not being one of those husbands who spend their

time in gambling, racing, women, wine, and song, tiring of their

wives and children as the little boy quickly tires of his childhood

toys. How thankful I am that you were not one of those husbands

who devote their time to growing rich on the exploitation of the

labor of others.

"Mrs.

Gandhi considers the Mahatma not as her husband but as her guru,

one who has the right to discipline her for even insignificant errors,"

I had pointed out. "Sometime after Kasturabai had been publicly

rebuked, Gandhi was sentenced to prison on a political charge. As

he was calmly bidding farewell to his wife, she fell at his feet.

'Master,' she said humbly, 'if I have ever offended you, please

forgive me.'"9

"Mahatmaji,"

I said as I squatted beside him on the uncushioned mat, "please

tell me your definition of ahimsa."

"Yes,

diet is important in the Satyagraha movementas everywhere

else," he said with a chuckle. "Because I advocate complete

continence for satyagrahis, I am always trying to find out

the best diet for the celibate. One must conquer the palate before

he can control the procreative instinct. Semi-starvation or unbalanced

diets are not the answer. After overcoming the inward greed

for food, a satyagrahi must continue to follow a rational

vegetarian diet with all necessary vitamins, minerals, calories,

and so forth. By inward and outward wisdom in regard to eating,

the satyagrahi's sexual fluid is easily turned into vital

energy for the whole body."

Gandhi's

face lit with interest. "I wonder if they would grow in Wardha?

The satyagrahis would appreciate a new food."

"I

will be sure to send some avocado plants from Los Angeles to Wardha."10

I added, "Eggs

are a high-protein food; are they forbidden to satyagrahis?"

On

the previous night Gandhi had expressed a wish to receive the

Kriya Yoga of Lahiri Mahasaya. I was touched by the Mahatma's

open-mindedness and spirit of inquiry. He is childlike in his divine

quest, revealing that pure receptivity which Jesus praised in children,

". . . of such is the kingdom of heaven."

The

hour for my promised instruction had arrived; several satyagrahis

now entered the roomMr. Desai, Dr. Pingale, and a few others who

desired the Kriya technique.

I first taught the little class the physical Yogoda exercises.

The body is visualized as divided into twenty parts; the will directs

energy in turn to each section. Soon everyone was vibrating before

me like a human motor. It was easy to observe the rippling effect

on Gandhi's twenty body parts, at all times completely exposed to

view! Though very thin, he is not unpleasingly so; the skin of his

body is smooth and unwrinkled.

Later

I initiated the group into the liberating technique of Kriya

Yoga.

The

Mahatma has reverently studied all world religions. The Jain scriptures,

the Biblical New Testament, and the sociological writings of Tolstoy11

are the three

main sources of Gandhi's nonviolent convictions.

He has stated his credo thus: I

believe the Bible, the Koran, and the Zend-Avesta12

to be

as divinely inspired as the Vedas. I believe in the institution

of Gurus, but in this age millions must go without a Guru, because

it is a rare thing to find a combination of perfect purity and perfect

learning. But one need not despair of ever knowing the truth of

one's religion, because the fundamentals of Hinduism as of every

great religion are unchangeable, and easily understood.

I

believe like every Hindu in God and His oneness, in rebirth and

salvation. . . . I can no more describe my feeling for Hinduism

than for my own wife. She moves me as no other woman in the world

can. Not that she has no faults; I daresay she has many more than

I see myself. But the feeling of an indissoluble bond is there.

Even so I feel for and about Hinduism with all its faults and limitations.

Nothing delights me so much as the music of the Gita, or

the Ramayana by Tulsidas. When I fancied I was taking my

last breath, the Gita was my solace.

Hinduism

is not an exclusive religion. In it there is room for the worship

of all the prophets of the world.13

It is not a missionary religion in the ordinary sense of the

term. It has no doubt absorbed many tribes in its fold, but this

absorption has been of an evolutionary, imperceptible character.

Hinduism tells each man to worship God according to his own faith

or dharma,14

and so lives

at peace with all religions.

Of

Christ, Gandhi has written: "I am sure that if He were living

here now among men, He would bless the lives of many who perhaps

have never even heard His name . . . just as it is written: 'Not

every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord . . . but he that doeth

the will of my Father.'15

In the lesson of His own life, Jesus gave humanity the magnificent

purpose and the single objective toward which we all ought to aspire.

I believe that He belongs not solely to Christianity, but to the

entire world, to all lands and races."

Night

was still lingering when I rose at 5:00 A.M. Village life was already

stirring; first a bullock cart by the ashram gates, then a peasant

with his huge burden balanced precariously on his head. After breakfast

our trio sought out Gandhi for farewell pronams. The saint

rises at four o'clock for his morning prayer.

War

and crime never pay. The billions of dollars that went up in the

smoke of explosive nothingness would have been sufficient to have

made a new world, one almost free from disease and completely free

from poverty. Not an earth of fear, chaos, famine, pestilence, the

danse macabre, but one broad land of peace, of prosperity, and

of widening knowledge.

"One

should forgive, under any injury," says the Mahabharata.

"It hath been said that the continuation of species is due

to man's being forgiving. Forgiveness is holiness; by forgiveness

the universe is held together. Forgiveness is the might of the mighty;

forgiveness is sacrifice; forgiveness is quiet of mind. Forgiveness

and gentleness are the qualities of the self-possessed. They represent

eternal virtue."

Epics

shall someday be written on the Indian satyagrahis who withstood

hate with love, violence with nonviolence, who allowed themselves

to be mercilessly slaughtered rather than retaliate. The result

on certain historic occasions was that the armed opponents threw

down their guns and fled, shamed, shaken to their depths by the

sight of men who valued the life of another above their own.

"I

would wait, if need be for ages," Gandhi says, "rather

than seek the freedom of my country through bloody means."

Never does the Mahatma forget the majestic warning: "All they

that take the sword shall perish with the sword."16

Gandhi has written: I

call myself a nationalist, but my nationalism is as broad as the

universe. It includes in its sweep all the nations of the earth.17

My nationalism

includes the well-being of the whole world. I do not want my India

to rise on the ashes of other nations. I do not want India to exploit

a single human being. I want India to be strong in order that she

can infect the other nations also with her strength. Not so with

a single nation in Europe today; they do not give strength to the

others.

By

the Mahatma's training of thousands of true satyagrahis (those

who have taken the eleven rigorous vows mentioned in the first part

of this chapter), who in turn spread the message; by patiently educating

the Indian masses to understand the spiritual and eventually material

benefits of nonviolence; by arming his people with nonviolent weaponsnon-cooperation

with injustice, the willingness to endure indignities, prison, death

itself rather than resort to arms; by enlisting world sympathy through

countless examples of heroic martyrdom among satyagrahis,

Gandhi has dramatically portrayed the practical nature of nonviolence,

its solemn power to settle disputes without war.

The

Mahatma is indeed a "great soul," but it was illiterate

millions who had the discernment to bestow the title. This gentle

prophet is honored in his own land. The lowly peasant has been able

to rise to Gandhi's high challenge. The Mahatma wholeheartedly believes

in the inherent nobility of man. The inevitable failures have never

disillusioned him. "Even if the opponent plays him false twenty

times," he writes, "the satyagrahi is ready to

trust him the twenty-first time, for an implicit trust in human

nature is the very essence of the creed."18

"It

is curious how we delude ourselves, fancying that the body can be

improved, but that it is impossible to evoke the hidden powers of

the soul," Gandhi replied. "I am engaged in trying to

show that if I have any of those powers, I am as frail a mortal

as any of us and that I never had anything extraordinary about me

nor have I now. I am a simple individual liable to err like any

other fellow mortal. I own, however, that I have enough humility

to confess my errors and to retrace my steps. I own that I have

an immovable faith in God and His goodness, and an unconsumable

passion for truth and love. But is that not what every person has

latent in him? If we are to make progress, we must

not repeat history but make new history. We must add to the inheritance

left by our ancestors. If we may make new discoveries and inventions

in the phenomenal world, must we declare our bankruptcy in the spiritual

domain? Is it impossible to multiply the exceptions so as to make

them the rule? Must man always be brute first and man after, if

at all?"19

"I

am fighting for nothing less than world peace," Gandhi has

declared. "If the Indian movement is carried to success on

a nonviolent Satyagraha basis, it will give a new meaning

to patriotism and, if I may say so in all humility, to life itself."

Before

the West dismisses Gandhi's program as one of an impractical dreamer,

let it first reflect on a definition of Satyagraha by the

Master of Galilee:

"Ye

have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth

for a tooth: but I say unto you, That ye resist not evil:20

but whosoever

shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also."

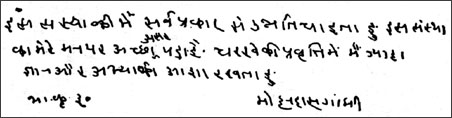

MAHATMA GANDHI'S HANDWRITING IN HINDI

Mahatma Gandhi visited my high school with yoga training at Ranchi.

He graciously wrote the above lines in the Ranchi guest-book. The

translation is: (Signed)

MOHANDAS GANDHI

(Gandhi himself

signed this page on the following day, giving the date alsoAugust

27, 1935.)

In this trifling

incident I noted the Mahatma's ability to detach his mind from the

senses at will. I recalled the famous appendectomy performed on

him some years ago. Refusing anesthetics, the saint had chatted

cheerfully with his disciples throughout the operation,

his infectious smile revealing his unawareness of pain.

"Rural

reconstruction work is rewarding! A group of us go every morning

at five o'clock to serve the near-by villagers and teach them simple

hygiene. We make it a point to clean their latrines and their mud-thatched

huts. The villagers are illiterate; they cannot be educated except

by example!" She laughed gaily.

I looked in

admiration at this highborn Englishwoman whose true Christian humility

enables her to do the scavengering work usually performed only by

"untouchables."

"I came

to India in 1925," she told me. "In this land I feel that

I have 'come back home.' Now I would never be willing to return

to my old life and old interests."

Gandhi has sound

economic and cultural reasons for encouraging the revival of cottage

industries, but he does not counsel a fanatical repudiation of all

modern progress. Machinery, trains, automobiles, the telegraph have

played important parts in his own colossal life! Fifty years of

public service, in prison and out, wrestling daily with practical

details and harsh realities in the political world, have only increased

his balance, open-mindedness, sanity, and humorous appreciation

of the quaint human spectacle.

Punctually at

eight o'clock Gandhi ended his silence. The herculean labors of

his life require him to apportion his time minutely.

"Welcome,

Swamiji!" The Mahatma's greeting this time was not via paper.

We had just descended from the roof to his writing room, simply

furnished with square mats (no chairs), a low desk with books, papers,

and a few ordinary pens (not fountain pens); a nondescript clock

ticked in a corner. An all-pervasive aura of peace and devotion.

Gandhi was bestowing one of his captivating, cavernous, almost toothless

smiles.

"Years

ago," he explained, "I started my weekly observance of

a day of silence as a means for gaining time to look after my correspondence.

But now those twenty-four hours have become a vital spiritual need.

A periodical decree of silence is not a torture but a blessing."

"Mahadev,"

Gandhi said as Mr. Desai entered the room, "please make arrangements

at Town Hall for Swamiji to speak there on yoga tomorrow night."

As

I was bidding the Mahatma good night, he considerately handed me

a bottle of citronella oil.

Noon found

me strolling about the ashram grounds, on to the grazing land of

a few imperturbable cows. The protection of cows is a passion with

Gandhi.

"The cow

to me means the entire sub-human world, extending man's sympathies

beyond his own species," the Mahatma has explained. "Man

through the cow is enjoined to realize his identity with all that

lives. Why the ancient rishis selected the cow for apotheosis is

obvious to me. The cow in India was the best comparison; she was

the giver of plenty. Not only did she give milk, but she also made

agriculture possible. The cow is a poem of pity; one reads pity

in the gentle animal. She is the second mother to millions of mankind.

Protection of the cow means protection of the whole dumb creation

of God. The appeal of the lower order of creation is all the more

forceful because it is speechless."

Reentering the

guest house I was struck anew by the stark simplicity and evidences

of self-sacrifice which are everywhere present. The Gandhi vow of

non-possession came early in his married life. Renouncing an extensive

legal practice which had been yielding him an annual income of more

than $20,000, the Mahatma dispersed all his wealth to the poor.

Sri Yukteswar

used to poke gentle fun at the commonly inadequate conceptions of

renunciation.

"A beggar

cannot renounce wealth," Master would say. "If a man laments:

'My business has failed; my wife has left me; I will renounce all

and enter a monastery,' to what worldly sacrifice is he referring?

He did not renounce wealth and love; they renounced him!"

Saints like

Gandhi, on the other hand, have made not only tangible material

sacrifices, but also the more difficult renunciation of selfish

motive and private goal, merging their inmost being in the stream

of humanity as a whole.

How thankful

I am that you put God and country before bribes, that you had the

courage of your convictions and a complete and implicit faith in

God. How thankful I am for a husband that put God and his country

before me. I am grateful to you for your tolerance of me and my

shortcomings of youth, when I grumbled and rebelled against the

change you made in our mode of living, from so much to so little.

As a young child,

I lived in your parents' home; your mother was a great and good

woman; she trained me, taught me how to be a brave, courageous wife

and how to keep the love and respect of her son, my future husband.

As the years passed and you became India's most beloved leader,

I had none of the fears that beset the wife who may be cast aside

when her husband has climbed the ladder of success, as so often

happens in other countries. I knew that death would still find us

husband and wife.

For years Kasturabai

performed the duties of treasurer of the public funds which the

idolized Mahatma is able to raise by the millions. There are many

humorous stories in Indian homes to the effect that husbands are

nervous about their wives' wearing any jewelry to a Gandhi meeting;

the Mahatma's magical tongue, pleading for the downtrodden, charms

the gold bracelets and diamond necklaces right off the arms and

necks of the wealthy into the collection basket!

One day the

public treasurer, Kasturabai, could not account for a disbursement

of four rupees. Gandhi duly published an auditing in which he inexorably

pointed out his wife's four rupee discrepancy.

I had often

told this story before classes of my American students. One evening

a woman in the hall had given an outraged gasp.

"Mahatma

or no Mahatma," she had cried, "if he were my husband

I would have given him a black eye for such an unnecessary public

insult!"

After some good-humored

banter had passed between us on the subject of American wives and

Hindu wives, I had gone on to a fuller explanation.

At three o'clock

that afternoon in Wardha, I betook myself, by previous appointment,

to the writing room of the saint who had been able to make an unflinching

disciple out of his own wiferare miracle! Gandhi looked up with

his unforgettable smile.

"The avoidance

of harm to any living creature in thought or deed."

"Beautiful

ideal! But the world will always ask: May one not kill a cobra to

protect a child, or one's self?"

"I could

not kill a cobra without violating two of my vowsfearlessness,

and non-killing. I would rather try inwardly to calm the snake by

vibrations of love. I cannot possibly lower my standards to suit

my circumstances." With his amazing candor, Gandhi added, "I

must confess that I could not carry on this conversation were I

faced by a cobra!"

I remarked on

several very recent Western books on diet which lay on his desk.

The Mahatma

and I compared our knowledge of good meat-substitutes. "The

avocado is excellent," I said. "There are numerous avocado

groves near my center in California."

"Not unfertilized

eggs." The Mahatma laughed reminiscently. "For years I

would not countenance their use; even now I personally do not eat

them. One of my daughters-in-law was once dying of malnutrition;

her doctor insisted on eggs. I would not agree, and advised him

to give her some egg-substitute.

"'Gandhiji,'

the doctor said, 'unfertilized eggs contain no life sperm; no killing

is involved.'

"I then

gladly gave permission for my daughter-in-law to eat eggs; she was

soon restored to health."

On my last evening

in Wardha I addressed the meeting which had been called by Mr. Desai

in Town Hall. The room was thronged to the window sills with about

400 people assembled to hear the talk on yoga. I spoke first in

Hindi, then in English. Our little group returned to the ashram

in time for a good-night glimpse of Gandhi, enfolded in peace and

correspondence.

"Mahatmaji,

good-by!" I knelt to touch his feet. "India is safe in

your keeping!"

Years have rolled

by since the Wardha idyl; the earth, oceans, and skies have darkened

with a world at war. Alone among great leaders, Gandhi has offered

a practical nonviolent alternative to armed might. To redress grievances

and remove injustices, the Mahatma has employed nonviolent means

which again and again have proved their effectiveness. He states

his doctrine in these words:

I have found

that life persists in the midst of destruction. Therefore there

must be a higher law than that of destruction. Only under that law

would well-ordered society be intelligible and life worth living.

If that is the

law of life we must work it out in daily existence. Wherever there

are wars, wherever we are confronted with an opponent, conquer by

love. I have found that the certain law of love has answered in

my own life as the law of destruction has never done.

In India we

have had an ocular demonstration of the operation of this law on

the widest scale possible. I don't claim that nonviolence has penetrated

the 360,000,000 people in India, but I do claim it has penetrated

deeper than any other doctrine in an incredibly short time.

It takes a fairly

strenuous course of training to attain a mental state of nonviolence.

It is a disciplined life, like the life of a soldier. The perfect

state is reached only when the mind, body, and speech are in proper

coordination. Every problem would lend itself to solution if we

determined to make the law of truth and nonviolence the law of life.

Just as a scientist

will work wonders out of various applications of the laws of nature,

a man who applies the laws of love with scientific precision can

work greater wonders. Nonviolence is infinitely more wonderful and

subtle than forces of nature like, for instance, electricity. The

law of love is a far greater science than any modern science.

Consulting history,

one may reasonably state that the problems of mankind have not been

solved by the use of brute force. World War I produced a world-chilling

snowball of war karma that swelled into World War II. Only the warmth

of brotherhood can melt the present colossal snowball of war karma

which may otherwise grow into World War III. This unholy trinity

will banish forever the possibility of World War IV by a finality

of atomic bombs. Use of jungle logic instead of human reason in

settling disputes will restore the earth to a jungle. If brothers

not in life, then brothers in violent death.

The nonviolent

voice of Gandhi appeals to man's highest conscience. Let nations

ally themselves no longer with death, but with life; not with destruction,

but with construction; not with the Annihilator, but with the Creator.

Nonviolence

is the natural outgrowth of the law of forgiveness and love. "If

loss of life becomes necessary in a righteous battle," Gandhi

proclaims, "one should be prepared, like Jesus, to shed his

own, not others', blood. Eventually there will be less blood spilt

in the world."

President Wilson

mentioned his beautiful fourteen points, but said: "After all,

if this endeavor of ours to arrive at peace fails, we have our armaments

to fall back upon." I want to reverse that position, and I

say: "Our armaments have failed already. Let us now be in search

of something new; let us try the force of love and God which is

truth." When we have got that, we shall want nothing else.

Gandhi has already

won through nonviolent means a greater number of political concessions

for his land than have ever been won by any leader of any country

except through bullets. Nonviolent methods for eradication of all

wrongs and evils have been strikingly applied not only in the political

arena but in the delicate and complicated field of Indian social

reform. Gandhi and his followers have removed many longstanding

feuds between Hindus and Mohammedans; hundreds of thousands of Moslems

look to the Mahatma as their leader. The untouchables have found

in him their fearless and triumphant champion. "If there be

a rebirth in store for me," Gandhi wrote, "I wish to be

born a pariah in the midst of pariahs, because thereby I would be

able to render them more effective service."

"Mahatmaji,

you are an exceptional man. You must not expect the world to act

as you do." A critic once made this observation.

Americans may

well remember with pride the successful nonviolent experiment of

William Penn in founding his 17th century colony in Pennsylvania.

There were "no forts, no soldiers, no militia, even no arms."

Amidst the savage frontier wars and the butcheries that went on

between the new settlers and the Red Indians, the Quakers of Pennsylvania

alone remained unmolested. "Others were slain; others were

massacred; but they were safe. Not a Quaker woman suffered assault;

not a Quaker child was slain, not a Quaker man was tortured."

When the Quakers were finally forced to give up the government of

the state, "war broke out, and some Pennsylvanians were killed.

But only three Quakers were killed, three who had so far fallen

from their faith as to carry weapons of defence."

"Resort

to force in the Great War (I) failed to bring tranquillity,"

Franklin D. Roosevelt has pointed out. "Victory and defeat

were alike sterile. That lesson the world should have learned."

"The more

weapons of violence, the more misery to mankind," Lao-tzu taught.

"The triumph of violence ends in a festival of mourning."

Gandhi's epoch

has extended, with the beautiful precision of cosmic timing, into

a century already desolated and devastated by two World Wars. A

divine handwriting appears on the granite wall of his life: a warning

against the further shedding of blood among brothers.

"This institution has deeply impressed my mind. I cherish high hopes

that this school will encourage the further practical use of the

spinning wheel."

September 17, 1925

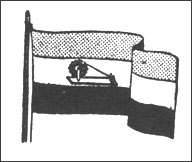

A

national flag for India was designed in 1921 by Gandhi. The stripes

are saffron, white and green; the charka (spinning wheel)

in the center is dark blue.

"The charka symbolizes energy," he wrote, "and reminds us

that during the past eras of prosperity in India's history, hand

spinning and other domestic crafts were prominent."

1

His family name is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He never refers to

himself as "Mahatma."

Back to text

2

The literal translation from Sanskrit is "holding to truth."

Satyagraha is the famous nonviolence movement led by Gandhi.

Back to text

3

False and alas! malicious reports were recently circulated that

Miss Slade has severed all her ties with Gandhi and forsaken her

vows. Miss Slade, the Mahatma's Satyagraha disciple for twenty years,

issued a signed statement to the United Press, dated Dec. 29, 1945,

in which she explained that a series of baseless rumors arose after

she had departed, with Gandhi's blessings, for a small site in northeastern

India near the Himalayas, for the purpose of founding there her

now-flourishing Kisan Ashram (center for medical and agricultural

aid to peasant farmers). Mahatma Gandhi plans to visit the new ashram

during 1946.

Back to text

4

Miss Slade reminded me of another distinguished Western woman, Miss

Margaret Woodrow Wilson, eldest daughter of America's great president.

I met her in New York; she was intensely interested in India. Later

she went to Pondicherry, where she spent the last five years of

her life, happily pursuing a path of discipline at the feet of Sri

Aurobindo Ghosh. This sage never speaks; he silently greets his

disciples on three annual occasions only.

Back to text

5

For years in America I had been observing periods of silence, to

the consternation of callers and secretaries.

Back to text

6

Harmlessness; nonviolence; the foundation rock of Gandhi's creed.

He was born into a family of strict Jains, who revere ahimsa as

the root-virtue. Jainism, a sect of Hinduism, was founded in the

6th century B.C. by Mahavira, a contemporary of Buddha. Mahavira

means "great hero"; may he look down the centuries on

his heroic son Gandhi!

Back to text

7

Hindi is the lingua franca for the whole of India. An Indo-Aryan

language based largely on Sanskrit roots, Hindi is the chief vernacular

of northern India. The main dialect of Western Hindi is Hindustani,

written both in the Devanagari (Sanskrit) characters and in Arabic

characters. Its subdialect, Urdu, is spoken by Moslems.

Back to text

8

Gandhi has described his life with a devastating candor in The Story

of my Experiments with Truth (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press, 1927-29,

2 vol.) This autobiography has been summarized in Mahatma Gandhi,

His Own Story, edited by C. F. Andrews, with an introduction by

John Haynes Holmes (New York: Macmillan Co., 1930).

Many autobiographies

replete with famous names and colorful events are almost completely

silent on any phase of inner analysis or development. One lays down

each of these books with a certain dissatisfaction, as though saying:

"Here is a man who knew many notable persons, but who never

knew himself." This reaction is impossible with Gandhi's autobiography;

he exposes his faults and subterfuges with an impersonal devotion

to truth rare in annals of any age.

Back to text

9

Kasturabai Gandhi died in imprisonment at Poona on February 22,

1944. The usually unemotional Gandhi wept silently. Shortly after

her admirers had suggested a Memorial Fund in her honor, 125 lacs

of rupees (nearly four million dollars) poured in from all over

India. Gandhi has arranged that the fund be used for village welfare

work among women and children. He reports his activities in his

English weekly, Harijan.

Back to text

10

I sent a shipment to Wardha, soon after my return to America. The

plants, alas! died on the way, unable to withstand the rigors of

the long ocean transportation.

Back to text

11

Thoreau, Ruskin, and Mazzini are three other Western writers whose

sociological views Gandhi has studied carefully.

Back to text

12

The sacred scripture given to Persia about 1000 B.C. by Zoroaster.

Back to text

13

The unique feature of Hinduism among the world religions is that

it derives not from a single great founder but from the impersonal

Vedic scriptures. Hinduism thus gives scope for worshipful incorporation

into its fold of prophets of all ages and all lands. The Vedic scriptures

regulate not only devotional practices but all important social

customs, in an effort to bring man's every action into harmony with

divine law.

Back to text

14

A comprehensive Sanskrit word for law; conformity to law or natural

righteousness; duty as inherent in the circumstances in which a

man finds himself at any given time. The scriptures define dharma

as "the natural universal laws whose observance enables man

to save himself from degradation and suffering."

Back to text

15

Matthew 7:21.

Back to text

16

Matthew 26:52.

Back to text

17

"Let not a man glory in this, that he love his country;

Let him rather glory in this, that he love his kind."-Persian

proverb.

Back to text

18

"Then came Peter to him and said, Lord, how oft shall my brother

sin against me, and I forgive him? till seven times? Jesus saith

unto him, I say not unto thee, Until seven times: but, Until seventy

times seven."-Matthew 18:21-22.

Back to text

19

Charles P. Steinmetz, the great electrical engineer, was once asked

by Mr. Roger W. Babson: "What line of research will see the

greatest development during the next fifty years?" "I

think the greatest discovery will be made along spiritual lines,"

Steinmetz replied. "Here is a force which history clearly teaches

has been the greatest power in the development of men. Yet we have

merely been playing with it and have never seriously studied it

as we have the physical forces. Someday people will learn that material

things do not bring happiness and are of little use in making men

and women creative and powerful. Then the scientists of the world

will turn their laboratories over to the study of God and prayer

and the spiritual forces which as yet have hardly been scratched.

When this day comes, the world will see more advancement in one

generation than it has seen in the past four."

Back to text

20

That is, resist not evil with evil. (Matthew 5:38-39)

Back to text

Contents |

Preface

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40:

41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

48

You are here: Home ![]() Spiritual Development

Spiritual Development ![]() Guides, Gurus and God-Beings

Guides, Gurus and God-Beings ![]()

![]()